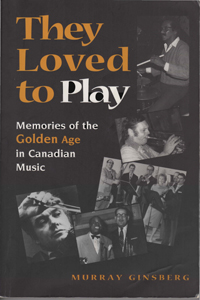

Excerpt from They All Love to Play by Murray Ginsberg

Excerpt from They All Love to Play by Murray Ginsberg

Published by eastendbooks, Toronto 1998 www.eastendbooks.com

Reprinted with permission of the copyright holder.

This book is out of print, but copies can be found at Abebooks.com

The basis of this is from an interview with Johnny Cowell in May, 1993

On July 18, 1991, the Toronto Symphony honoured trumpeter Johnny Cowell with a special tribute concert, to mark his retirement from the orchestra. After thirty-nine years as a member of the trumpet section, the TS management chose to roll out the red carpet for this special musician–the first event of its kind in the orchestra’s history.

Why the unprecedented celebration? Simple, Johnny Cowell had brought an unprecedented degree of honour and prestige to the orchestra: not least by his ability to pack a hall when entertaining a pops-concert audience. As if his excellence in the TS trumpet section were not enough, over a career spanning more than fifty years he had also become one of Canada’s top composers of popular songs. And many of his songs had become hits, recorded by more than 100 top international stars.

When tastes in music changed from the soothing love ballads to rock and roll, Johnny changed too. With such recording artists as Tony Martin and Andy Williams no longer fashionable, Cowell turned to composing light instrumental novelties for symphony orchestras. Out of his fertile creative mind sprung the likes of Girl on a Roller-Coaster, Famous Trumpeters, and Canadian Odyssey.

The 1991 tribute was a sold-out success. Conducted by Newton Wayland, it featured most of Cowell’s hit songs, as well as his later instrumental pieces, much to the delight of the audience. Many friends and colleagues were on hand, along with his wife of fifty years, Joan Mitchell Cowell. Finally, when the lights at Roy Thomson Hall were turned off, Johnny and Joan returned to their home in suburban Scarborough.

With his symphony days over, did the trumpet player quit his beloved profession? Not likely. A musician who loves to play as much as Johnny Cowell, never gives up.

As I write today, he is far from retired. At a time in life when most musicians have packed away their instruments, the trumpeter still practises long hours and performs with various groups, like the Hannaford Street Silver Band, which gives periodic concerts at the St. Lawrence Centre for the Performing Arts. His mind still swims with musical ideas. And ultimately he reaches for his pen and, once again, he starts to compose.

Born in 1926 in Tillsonburg, a small town in the old tobacco-growing district of southwestern Ontario, Johnny was only six years old when, accompanied by his mother on the piano, he played his first solo. His trumpet was a “battered antique” which his uncle had given him the year before. As Johnny told me in an interview in May, 1993:

It was the greatest gift I’d ever received. It was so beat up and dented that the valve caps had to be replaced with pennies. But I didn’t care. I wanted to play the trumpet.

Although Tillsonburg had no professional brass teachers to speak of in 1932, Johnny’s father played trombone and his uncle played trumpet in the town band.

I sort of picked it up just by watching them.

Blessed with a keen musical ear, the lad experimented with producing a sound, discovering which valves to press down to get certain notes, and how to play simple melodies:

I sort of flopped around on it and got something going.

By the time he was eight Johnny was not just a member of the Tillsonburg town band, but a featured soloist as well:

My mother wrote the arrangements for me. One year they featured me on an annual spring concert when Captain John Slatter, conductor of the 48th Highlanders Band, was the guest conductor. I played two solos with the band and Captain Slatter said he would see me again one day. He was true to his word. I met him years later when I came to Toronto and played with his band a couple of times as soloist.

Rehearsals with the Tillsonburg band took place every Thursday evening, the same night the Toronto Symphony Band performed a weekly one-hour CBC radio broadcast. The band, a thirty-five piece ensemble, comprised mainly of Toronto Symphony Orchestra brass, woodwind and percussion players, was conducted by “Puff” Addison, a rotund, obstreperous rhinoceros. Johnny recalls:

I used to rush home from our band practice to hear the broadcast which almost always featured their cornet soloist, Ellis McLintock, who I thought was wonderful. That was in 1941.

Little did the young Cowell realize at the time that within a year he would sit in Ellis McLintock’s chair in that band. During a broadcast one evening in 1942, the announcer reported that eighteen-year-old Ellis was going into the Air Force as the cornet soloist of the RCAF Band. The Toronto Symphony Band was looking for a replacement. Cowell was fifteen at the time. He wrote a letter to Puff Addison asking for an audition, but made a point of omitting his age. The bandmaster wrote back, asking him to come to Toronto, and included his home address.

Johnny carried on with the story at our May, 1993 interview:

I got a lift on an early transport truck to Toronto and took a streetcar to Columbine Avenue, in the east end, and looked for Addison’s house. I knocked on the door for about five minutes before he opened it. You’ve gotta see Puff in his pajamas. He was madder’n hell. “Yeah? What the hell do you want?” he yelled

I’m Jack Cowell.” (Puff later changed his name to John.) “I wrote you a letter, remember? You asked me to come on down to audition for Ellis’ job.”

“What? How old are you?” he asked.

“Fifteen.”

“You can’t audition for our band. You’re just a kid. We can’t even hire you. You’ve got to be sixteen to join the union.”

“So it’s a wasted trip,” I said. “Well, I came all the way down here just to play for you.”

“Well–ll, alright, he grunted. Come on in.”

I went into the house and followed him into his studio which was three by three (pretty crowded since Puff was three by three). Anyway, at nine o’clock in the morning I played some solos for him. He liked it. “Can you stay over in Toronto and come to Varsity Arena tomorrow morning? I want the guys in the band to hear you play.” So he arranged to have me stay at a friend’s house.

The next morning Johnny went to Varsity Arena and auditioned for the Toronto Symphony Band Committee. After hearing the first few passages they knew immediately that the young musician could fill Ellis’ chair. But how to get around the union rules? Puff Addison phoned the union and explained the situation to Local 149 president, Walter Murdoch. The president quickly arranged a special “junior” membership of Jack Cowell who, with a stroke of the pen, became a union member of the Toronto Symphony Band, and a cornet soloist–all in one fell swoop. As Johnny summed things up at our 1993 interview:

That’s how I got into the music business. Got Ellis’ old job.

Up until the time Johnny played with the Toronto Symphony Band, he had never had a teacher. He was literally self-taught. He was playing solos and executing all the technical passages with great facility, but only as an inexperienced youngster would play them.

His life soon took a turn for the better. Harry Hawe, the principal trombonist of both the Toronto Symphony Orchestra and the Toronto Symphony Band (and, as some readers may remember, my own music teacher as well), took Johnny aside. Born in Toronto, Hawe was a master trombonist who had played and soloed with some of the world’s top concert bands, including the famed Franko Edwin Goldman Band in the United States. Hawe told Johnny, “You’re playing those solos really well, but your interpretation is a little bit different than what it could be. Would you like to know how to interpret them properly?”

“Sure,” Johnny enthusiastically replied. So every time he had a solo to play he would go to Hawe’s house for a lesson. Before the lesson began, the trombonist would play such pieces as The Carnival of Venice, Bride of the Waves, and The Debutante, all designed to impress the boy with how solos should be performed. He would then play a few bars of Cowell’s solo and say, “This is what you’re doing.

Then he’d play the same bars and say, “This is how Herbert Clarke plays it.” (Herbert Clarke was a trumpet authority of the day, with whom Johnny was already familiar.) Johnny never forgot the master’s advice.

By the time he was sixteen, Johnny was playing with the Toronto Symphony Orchestra:

Bert Jones, who played with the TSB, also played with the TSO. Bert was ill a lot of the time, and when he couldn’t perform with the orchestra I was called to fill in. I played second trumpet to Morris Isenbaum, who had taken over from Ellis when he went into the Air Force.

Soon enough Johnny was playing with the symphony more than Bert Jones.

The following year I was offered the chance to be the soloist.

By this time the original “Jack Cowell” from Tillsonburg had already left his earlier identity behind. When he’d arrived for his very first rehearsal with the Toronto Symphony Band, Puff Addison had introduced him to the band members.

With his cigarette popping up and down and the ashes falling all over his shirt, Puff said gruffly, “Okay, gentlemen, this here’s Jack Cowell. He’s from Tillsonburg, wherever the hell that is. We got two Jacks in the band now. And one more Jack is just one too many. So, from now on, we’re going to call him John. It’s the same as Jack; so his name is John.” And from John, the guys started calling me Johnny. I really had nothing to do with changing my name.

Even with his new name, the Second World War caught up with Johnny when he turned seventeen. He joined the Canadian Navy’s HMCS Naden Band as a cornet soloist, in Esquimalt, British Columbia.

When I was in the band I got to be first trumpet with the Victoria Symphony, and also got to play a little dance work. On Friday and Saturday nights I’d play with a Dixieland band, and then I joined the navy dance band. We were playing all the time–cornet solos almost daily with the navy band, playing daily and twice-daily parades, beating my Dixieland feet on the Mississippi mud of the Esquimalt jazz band on weekends, and screeching high notes in the Naden Big Band dances.

Then there was a day he will never forget: August 14, 1945–VJ Day–the day Japan surrendered to the Allies.

I played a concert in the morning, then another concert later in the day. Then we did a parade, and still another concert, and then a second parade (three concerts and two parades), followed by a street dance at night. The gig started at 8:00 p.m. and went to 1 a.m.

The next morning Johnny took his trumpet out to practise and put the mouthpiece to his lips. When he blew, to his great surprise, he found he couldn’t get a sound:

I looked in the mirror and saw something was wrong with my lip. All the tissues were split.

Horrified, he went to the medical officer and told him what he had done the day before:

The doctor told me there was nothing he could do for me, but he would send me to a Vancouver specialist. After the specialist examined my lip, he looked me in the eye and asked, “How do you like it in the navy?”

“Okay, I guess,” I said

“You sure you don’t want to get out?”

“How can I get out?” I countered

“Well, you’re a bandsman,” the doctor said. “I can tell you you’ll never play again as long as you live. All the tissues are severed. There’s just a little piece of skin left. That’s from playing for such a long time.”

Johnny was mortified:

I didn’t realize what I was doing. I was too stupid to know. I just screwed it up completely. And so, after two years of service the authorities released the nineteen-year-old from the navy, right after VJ Day.

Back in Toronto, Johnny pondered his future. The prospect of working in a factory didn’t appeal to him. He tried playing again, to no avail.

There was nothing there. I couldn’t get a note; so I left it alone.

He put his trumpet in its case and tried to forget about it–a tragedy for a man whose entire existence had been music and performing. Forgetting what he loved most, however, was easier said than done. The spirit of music permeated his mind and soul:

I wanted to be in music so much that I started writing. I knew nothing about composition or orchestration, so I got a couple of scores of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. Then I studied them, figured them out, and wrote a Suite for Orchestra –for full symphony orchestra–and submitted it to the Royal Conservatory in Toronto. They thought it good enough to present me with a scholarship.

At the Conservatory he studied orchestration with John Weinzweig, but the trumpet was never beyond his reach. Every so often he would put it to his lips. One day, miracle of miracles, a note, a vibration, sounded from the bell of the trumpet. Encouraged, Johnny began to practise, slowly at first, then a little more every few days:

It got so I could play, not well, but at least something, anything, a melody or two.

He never forgot how to play. He knew all the fingerings, but his embouchure was weak. He kept trying, practising all the exercises that students practice to gain strength, like a baby learning to walk.

Then I met Don Johnson who was in the Toronto Symphony and we soon became inseparable. Don said he would get me into Stanley St. John’s orchestra. I told him I couldn’t play more than fifteen or twenty minutes, then I’m finished. He said, “Don’t you worry, I’ll carry you.” This was about three years that I hadn’t played. What I was getting was only a G on top of the staff; that was my highest note. But Don was such a good friend that he did exactly what he said. I’d get on the job with him and if there was any little second trumpet stuff to do and I was shot, he would cover me.

In the mean time Johnny was gaining a little more strength each time he played:

It took me quite a while to get back in shape, and I was just in the right place at the right time when my chops really started to come back. That’s when Don left the symphony, which created an opening for third trumpet.

Auditions were called in 1952 and almost every trumpet player in the city applied for the position:

There must have been twenty of us waiting outside the audition room at the Conservatory to be called in. Sir Ernest MacMillan and all the principal players of each section were in there as well. Each guy would go in to Sir Ernest’s office, which was a very small, crowded room, and we’d hear him play a few excerpts. Then you heard about sixteen bars of the Haydn Trumpet Concerto. Then they would come out. And this went on and on.

Finally it was my turn. After I played my excerpts, Sir Ernest asked, “Now we’ll play a few bars of the Haydn Trumpet Concerto. Do you know that?” After I’d played the first sixteen bars and he said, “Keep playing,” I played the whole movement. When he didn’t stop me I knew I had the job. I wound up playing the entire concerto, but nothing was said. Sir Ernest was such a nice guy. He wanted to be fair and allowed every trumpet player to get a crack at it.

In the end it was weeks before the TSO personnel manager called Johnny Cowell. By then he was playing with Joe McNealy’s band in Wasaga Beach for the summer. His mother took the message, and telephoned him with the good news.

After years of playing jobs, particularly one-trumpet jobs, where I was embarrassed because I would be shot at 9:15 p.m., and had to suffer ‘til 12:30 or one in the morning, I finally made it. It had been a long time fighting back. I don’t know why those guys ever called me again, when they knew I didn’t have the chops.

While playing with Stanley St. John, Johnny had met Joan Mitchell, the band’s beautiful raven-haired singer, whom he eventually married:

She was a good-looking chick. I figured I had to impress her somehow. So I started writing songs for her. She’d come over to my place and we’d play my songs. I played the piano. (I didn’t have any lessons, I just picked it up.) We got going, making pretty good music together–on the couch. We got married in 1953, when I was in the Toronto Symphony.

Johnny’s interests in songs and singing had already had a boost when he left Stanley St. John to play third trumpet with Art Hallman, one of Toronto’s most successful band leaders in the postwar years:

What Art really wanted was a male singer for his vocal group, not a trumpet player…The thing that saved me was that I could sing the harmony parts without a problem, all the notes in tune. I wasn’t much of a singer–Art soon found that out–but he was impressed with my ability to blend in with the other singers. I stayed with Art until 1952 when I auditioned for the Toronto Symphony.

When he became a member of the TSO, Johnny was twenty-seven. By this time his trumpet embouchure (or the strength and control in his lips) had improved significantly. In May 1993 he told me that:

My embouchure was back but not to the point that it is now. I have better endurance now, better range than I’ve ever had.

(Very few professional brass players who suffer total loss of an embouchure ever experience a rebirth, as I would much later learn so well myself. In this, as in other respects, Johnny Cowell was one in a million.) By this point also, the singing (or at least song-writing ) part of his musical career had also taken a fresh lease on life.

I actually starting writing songs in earnest when I joined the symphony. When I left Art Hallmann, I went with Johnny Linden, at the Royal York Hotel, Johnny was a good looking guy and a terrific entertainer. The audience loved him. He and I were good friends…That’s when I started writing a lot of songs.

Someone who happened to work with Broadcast Music Incorporated in the U.S.A. heard one of the songs Johnny wrote for Linden at the Royal York (and for band vocalist Shirley Harmer), and this led to a song writing contract with Harold Moon at BMI.

Then in 1955, Johnny was playing on the CBC’s Denny Vaughan television show when Denny, a good friend, said, “I’m doing a recording session December 31. Do you have any songs I could do?” As Johnny recalls the story from here:

I brought Walk Hand in Hand which he recorded and released in Canada. Everybody said it was a pretty tune but it made very little noise. Denny thought it wasn’t taking off in Canada the way it should. So he took his record to Republic Music in New York, Sammy Kaye’s publishing company.

As fate would have it, Sammy Kaye took the tune to Archie Blyer at Cadence Records. (Archie Blyer had the band for the Arthur Godfrey Show.) Cadence took it to the people at RCA records, who were looking for a song for Tony Martin (whose popularity had recently taken a nosedive). RCA told Martin to record it, and his version of Johnny Cowell’s song became number one all over the world, catapulting the singer to the top once more. Johnny still remembers the thrill he got when Tony Martin walked out on stage on the Ed Sullivan Show from New York and sang Walk Hand in Hand. When it was released in England it became even bigger.

Then Andy Williams recorded the song, and other artists followed suit, each hoping to cash in on the hit that remained at the top of the charts for a record thirty-three weeks. Meanwhile, BMI’s statements to Johnny revealed a spectacular number of performances, growing every month and followed by lucrative royalty cheques as well. Johnny told me in 1993:

I finally met Tony Martin. He said, “Hey you go another Walk Hand in Hand for me? I said, Yeah, I got about four of them. So he took them and I never heard from him again. Nice guy. And they were good songs, too.

The climb to prominence of another of Johnny Cowell’s greatest hits began when Chet Atkins phoned from New York, sometime in 1963. “Al Hirt’s doing a recording session in about six weeks and we’re looking for something for Al to play,” he said: “something different. Your name came up, and since you’re a trumpet player and a writer, would you write something for Al and send it down to us?”

Johnny went to his den and very quickly put the finishing touches on a tune he’d been calling Long Island Sound. Usually he wrote his own lyrics, but in this case, he didn’t have any lyrics for it:

I didn’t have time to work on any, so I sent it off as it was.

Then Chet Atkins called from New York to ask if he could change the title.

“What do you want to change it to?” asked Johnny.

“One of our associates has come up with the idea of called it Our Winter Love. It’s bound to get a lot of air play.” Chet Atkins went on. “If it gets to be a hit, we think the title will ensure a lot of air play every year, in season.”

Chet Atkins’ associate was right. Every year now, for decades, just after the hectic Christmas and New Years’ seasons have come and gone, pianist Bill Purcell’s deeply moving rendition of Our Winter Love is heard on radio stations in several parts of the world. Johnny remarked during our 1993 interview:

It’s incredible; those guys really think of everything. When I got my statements from the company I would see 20,000 performances in the United States in a quarter–from December through to the end of April. Then they’d drop off until the next November, when the song again got thousands of logged performances. Our Winter Love worked really well in the United States and England.

I can add one minor observation on the creative process here myself. Prior to a Toronto Symphony rehearsal in Massey Hall, one cold morning in 1963, when the orchestra room was a din, as musicians warmed up on the instruments, I remember seeing Johnny Cowell standing near the telephone at one end of the room.

With a cup mute in the bell of his trumpet to soften the sound, he was running over a melody he had been thinking about to see how it would fly. I realized at the time I was witness to one of the composer’s moments of inspiration. That melody blossomed to become Our Winter Love.

The vagaries of public taste have long mystified composers whose songs may be the most beautiful ever written, but for some reason never become big sellers. During his song writing career, Johnny Cowell has written about 150 songs, of which about 100 have been recorded by different artists. A few of the recorded songs have become great hits, but most of them have fallen by the wayside (which as Johnny says himself, “most songs do”).

Apart from his initial collaboration with Chet Atkins on Our Winter Love, Al Hirt recorded several other Johnny Cowell inventions, but Strawberry Jam was the only one that made it to the charts. His Girl, a song Johnny wrote for The Guess Who’s first recording session, had to rest content with “Number One in Canada,” though Johnny still likes to remember:

His Girl, was also number one on that 1960s off-shore pirate station, Radio Caroline, in England.

Even so, it takes more than the fingers of one hand to count all the Johnny Cowell songs that have not quite fallen by the wayside. In his song writing, as in his trumpet playing, Johnny Cowell’s luck has often enough come pretty close to matching his talent. And he’s still a man who never gives up.

There is of course, giving up and giving up. And in one sense, Johnny did almost give up on writing at least certain kinds of songs:

When Elvis Presley and The Beatles moved in with the rock stuff…I didn’t want to change my style of writing, because that’s what I was good at. So I switched to writing symphonic pops and it worked out just at the right time.

As a member of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra in the 1960s he became friends with the American conductor, Erich Kunzel, who was brought in to preside over the orchestra’s pops concerts. Aware of Cowells’ enormous talent, Kunzel kept asking him to write something. Johnny was intrigued, but he hesitated until Seiji Ozawa, the orchestra’s permanent conductor, asked for an original composition to play as an encore piece for the TSO’s tour of Japan, in September, 1969.

Girl on a Roller-Coaster, which featured the trumpet section executing a series of technically difficult passages, dazzled the Japanese audiences. Then when Andrew Davis replaced Ozawa, he asked Johnny to compose a piece for the orchestra’s final concert at Massey Hall, on Shuter Street (before moving to its new home, at Roy Thomson Hall, on King Street). And the resulting A Farewell Tribute to the Grand Old Lady of Shuter Street thrilled the audience in the TSO’s home town.

Other pieces followed in a similar vein. They included Famous Trumpeters –a forty-minute tribute to such legendary artists as Louis Armstrong, Harry James, and Bunny Berigan, and Canadian Odyssey (a commemoration of the TSO’s tour of Canada’s sometimes forbidding but always majestic Northwest Territories).

Johnny also managed to bring some of the spirit behind his symphonic-pops writing career into his mature trumpet playing. He recorded a number of albums of “classical music hits.” They were cheered and applauded by music lovers, and won praise from Johnny’s peers around the world. (One morning after his album, Carnival of Venice, had been released, the telephone in Johnny’s Scarborough home erupted in a loud ring. Wife Joan picked up the receiver. “Is Johnny Cowell there?” a voice asked. When Joan called Johnny to the phone, he asked who it was. “I don’t know. Probably Doc Severinsen wanting to take lessons,” she joked. It was in fact the renowned trumpeter Doc Severinsen, phoning from New York to say how much he had enjoyed Carnival of Venice.)

Officially, Johnny Cowell has been retired from the music business, ever since the special tribute concert of July 18, 1991, which commemorated the end of his thirty-nine years in the trumpet section of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra. But someone who loves his work as much as he does never really retires. As he explained at the end of our 1993 interview, his mind still swims with ideas, which ultimately lead him to his pen and manuscript paper.

Save